The increased risk for suicide in those experiencing from PTSD is well known. For example, Gradus et al., 2010 studied of a large sample of the Danish population (n = 208,918). They reported persons with PTSD had 5.3 times the rate of death from suicide than persons without PTSD. This included after adjustment for gender, age, marital status, income, and pre-existing depression diagnoses. Similarly, several others have noted an elevated suicide risk in those experiencing chronic PTSD; Tarrier & Gregg (2004), Krysinska & Lester (2010), Pompili et al., (2013).

Many clinicians fear that by treating PTSD they may push a client too far and trigger strong emotional reactions that lead to suicidal ideation, and an attempt. But what does the research say?

This blog will review some of the research related to CPT for PTSD and suicidal ideation.

2017

In her study of Effect of Group vs Individual Cognitive Processing Therapy in Active-Duty Military Seeking Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Resick et al. (2017) also assessed suicidal ideation. Her team’s study had an exclusion criterion that consisted of suicidal or homicidal intent or psychosis. They measured suicidal ideation using the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI). The BSSI is purported to measure three factors:

- Active Suicidal Desire

- Specific Plans for Suicide

- Passive Suicidal Desire

Resick et al. (2017) reported that the proportions of suicidality as measured by the BSSI dropped in both group and individual treatment arms during treatment (overall effect of time, χ2 2 = 13.0; P = .002).

Resick et al. (2017) study also reported on adverse events. Seventeen psychological events were judged by the participants to be at least possibly related to the study, and these occurred because of increased symptoms evoked by baseline assessment procedures (4 patients) or the trauma focus of therapy (7 patients in group CPT and 6 patients in individual CPT). Resick et al. (2017) described that most of the psychiatric adverse events were common symptoms of PTSD observed in the study population (military with PTSD).

During the study, two unsuccessful suicide attempts occurred in patients randomized to group CPT (one before the start of treatment and one during treatment); neither was judged to be study related as per participant report.

Resick et al. (2017) summarised that Cognitive Processing Therapy did not increase suicidal ideation on the BSSI or reported adverse effects despite the trauma focus. In fact, they observed a significant and steady decrease in suicidal ideation in both treatment formats.

2018

Holliday et al. (2018) completed a preliminary examination of decreases in suicide cognitions after Cognitive Processing Therapy among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder due to military sexual trauma ( see below for more info on MST).

The study had some limitations due to a small sample size. Holliday et al. (2018) had 32 participants in their sample, 22 (68.8%) completed all 12 sessions of CPT, with an average of 9.94 (SD = 3.27) CPT sessions completed.

They used the Suicide Cognitions Scale (SCS). This measure is an 18-item self-report questionnaire composed of three latent factors of suicide-specific beliefs:

- unbearability (e.g., “I can’t stand this pain anymore”)

- unlovability (e.g., “I am completely unworthy of love”)

- unsolvability (e.g., “suicide is the only way to solve my problems”)

Participants were administered the SCS at 1 week, 2 months, 4 months, and 6 months posttreatment. During CPT and posttreatment participants experienced a significant reduction in beliefs regarding:

- unbearability (b = −3.15, t[31] = −4.72[.67], p < 0.001)

- unlovability (b = −2.20, t[31] = −4.05[.54], p < 0.001)

- unsolvability (b = −1.22, t[31] = −2.49[.49], p = 0.019)

The study had limitations due to the small sample size. However, the authors concluded:

“These findings provide preliminary evidence that a standard course of CPT may have the potential to reduce suicide specific beliefs in veterans with MST-related PTSD.” pg 577

2021

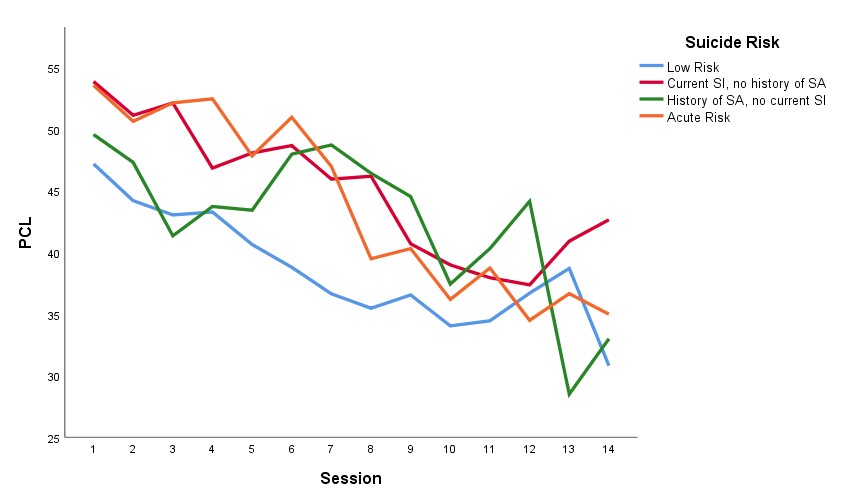

Roberge et al. (2021) examined the effect of using CPT to treat veterans experiencing PTSD and suicidal ideation. The participants in her groups study screened well above the PCL-5 threshold (33) for PTSD, with a mean PCL-5 score of 50.70 (SD = 13.77).

The sample characteristics included:

- 42% current suicidal ideation

- 5% history of attempted suicide

- 46% low risk

- 10% acute risk of suicide

Roberge and colleagues 2021 also used two different categorisations methods to define elevated and low risk. These methods considered combinations of the following factors:

- history of suicide attempts

- absence of attempt

- recent and/or current suicidal ideation

- absence of recent and/or current suicidal ideation

They determined that most veterans who engaged in CPT were at increased risk for suicide as determined by these clinical factors. Given a picture says a thousand words this graph from the study shows the effects of CPT treatment for the various groups over a course of CPT for PTSD

Other important finding that Roberge and colleagues 2021 reported included;

- High risk veterans were just as likely to complete treatment as low risk veterans.

- Suicide risk groups experienced similar levels and rate of PTSD symptom change over the course of treatment.

- On average, veterans reported clinically significant reduction of PTSD symptoms.

Of particular interest to clinicians concerned about risk is Roberge and colleagues’ statement about treatment safety.

“Three veterans (1.0%) engaged in suicidal behaviour (i.e., suicide attempt) between treatment initiation and the chart review process (i.e., August 2020). Of these veterans, all endorsed suicidal ideation at the time of treatment initiation, and two had prior histories of suicide attempts. Two veterans’ attempts occurred approximately seven months after CPT, whereas the other veteran’s attempt occurred in the month following their first and only CPT session. According to local records, to date, no veterans who engaged in CPT between 2016 and 2018 have died by suicide.” (p.4)

Summary

CPT for PTSD can be safely and effectively delivered to individuals with increased risk for suicide and appears to result in a reduction in ideation as well as PTSD symptoms.

What is Military Sexual Trauma (MST)

Survivors of MST often work alongside their perpetrators and the can have the experience that the military does not take action. There can be negative consequences for reporting MST and stigma. MST happens in the context of the military hierarchy. MST can happen in the context of operations where fellow soldiers are protecting each other’s lives when in danger.

References

Holliday, R., Holder, N., Monteith, L. L., & Surís, A. (2018). Decreases in suicide cognitions after cognitive processing therapy among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder due to military sexual trauma: A preliminary examination. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 206(7), 575–578. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000840

Jaimie L. Gradus, Ping Qin, Alisa K. Lincoln, Matthew Miller, Elizabeth Lawler, Henrik Toft Sørensen, Timothy L. Lash, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Completed Suicide, American Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 171, Issue 6, 15 March 2010, Pages 721–727, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwp456

Krysinska, K., & Lester, D. (2010). Post-traumatic stress disorder and suicide risk: a systematic review. Archives of suicide research : official journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research, 14(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811110903478997

Pompili, M., Sher, L., Serafini, G., Forte, A., Innamorati, M., Dominici, G., Lester, D., Amore, M., & Girardi, P. (2013). Posttraumatic stress disorder and suicide risk among veterans: A literature review. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 201(9), 802–812. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182a21458

Resick, P. A., Wachen, J. S., Dondanville, K. A., Pruiksma, K. E., Yarvis, J. S., Peterson, A. L., & Mintz, J. (2017). Effect of group vs. individual cognitive processing therapy in active-duty military seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(1), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2729

Roberge, E.M., Harris, J.A., Weinstein, H.R., & Rozek, D.C. (2021). Treating veterans at risk for suicide: An examination of the safety, tolerability, and outcomes of cognitive processing therapy. Journal of Traumatic Stress.

Tarrier, N., & Gregg, L. (2004). Suicide risk in civilian PTSD patients–predictors of suicidal ideation, planning and attempts. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 39(8), 655–661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-004-0799-4

Parts of this blog also appeared on https://psychpd.com.au/category/ptsd/